Tea Classification: From Experience to Theory

China is the only country in the world that produces all six major categories of tea: green, white, yellow, oolong, black, and dark tea. Each category has its own unique history, characteristics, and benefits.

In ancient China, tea classification was largely based on empirical and sensory observations such as appearance and color, and it varied with the dynasties. For instance, the Tang dynasty’s Classic of Tea (Cha Jing) mentions “coarse tea, loose tea, powdered tea, and cake tea.” The History of Song records “two types of tea: brick tea and loose tea.” In the Yuan dynasty, loose tea was divided into “bud tea” and “leaf tea” based on the tenderness of the fresh leaves. By the Ming dynasty, distinctions for green, yellow, black, white, and red tea already existed, and records of Qingcha (Oolong tea) appeared in the Qing dynasty. However, these names did not fully describe the characteristics of each tea type, nor did they provide a theoretical basis for classification.

In the modern era, China’s vast tea family has been categorized by various standards, such as the degree of fermentation or withering, the season of harvest, the shape of the processed tea, production techniques, types of flower scenting, region of origin, and consumer markets. Because these classifications served different purposes, they were generally only applicable in specific contexts. This lack of a unified standard created confusion and conflict in wider-scale production, trade, and statistics.

In 1978, tea scholar Chen Chuan proposed in his paper, The Theory and Practice of Tea Classification, that “tea classification is a specialized discipline. A precise and systematic classification should clearly illustrate the developmental process and interrelationships between tea categories, showcasing the systemization of quality and production methods. It allows us to observe the process of change from quantity to quality.” This provided the theoretical foundation for the modern classification of the six major tea categories.

Based on differences in production methods and quality, Professor Chen classified tea into six major categories according to the sequential order of flavanol content: green tea, yellow tea, dark tea, white tea, oolong tea, and black tea. This system not only retained the historically recognized tea names derived from experience, making them easy to distinguish, but also aligned with the principles of the tea’s internal chemical changes.

Green Tea: “Half the Kingdom” of Chinese Tea

In terms of fermentation, green tea is unfermented (zero fermentation) and is the most produced category of tea in China. The basic production process involves three main steps: fixation (kill-green), rolling, and drying.

Fixation can be done through heat, known as pan-firing (chǎoqīng), or with steam, known as steaming (zhēngqīng). Drying methods include pan-drying, baking, and sun-drying. Green tea that is pan-dried is called “pan-fired green tea” (chǎoqīng), baked is “oven-dried green tea” (hōngqīng), and sun-dried is “sun-dried green tea” (shàiqīng). Since pan-fired green tea became popular in the Ming dynasty, tea artisans across the country continuously innovated the firing process, creating numerous pan-fired green teas with distinctive shapes and qualities, such as Songluo tea from Huizhou, Longjing from Hangzhou, and Guapian from Lu’an.

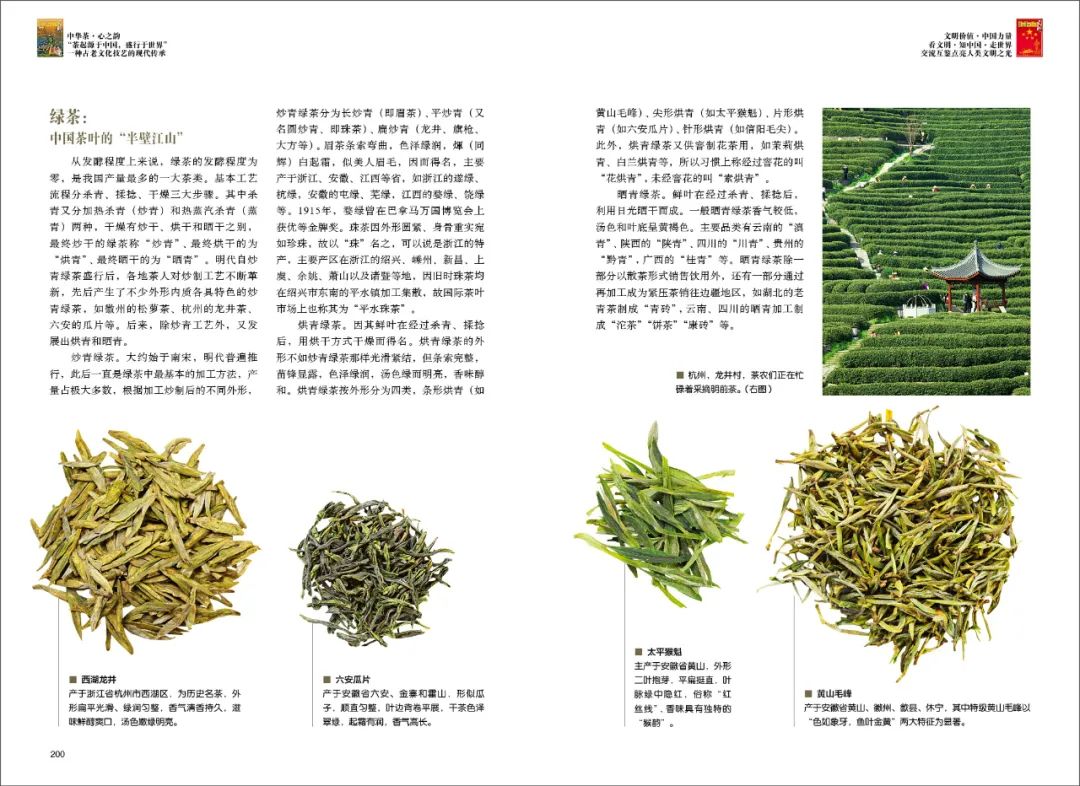

Pan-fired Green Tea (Chǎoqīng). Originating around the Southern Song dynasty and becoming widespread in the Ming dynasty, this has remained the most fundamental processing method for green tea, accounting for the vast majority of its production. Based on the final shape after firing, it is divided into long-fired (e.g., Mei Cha or “eyebrow tea”), round-fired (e.g., Zhu Cha or “gunpowder tea”), and flat-fired (e.g., Longjing, Qiqiang, Dafang).

Mei Cha features curved, lustrous green leaves with a white, frost-like sheen, resembling a woman’s eyebrow, hence the name. It is primarily produced in provinces like Zhejiang, Anhui, and Jiangxi. In 1915, Wuyuan Green Tea (Wùlǜ) won a gold medal at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition.

Zhu Cha is named for its round, tightly rolled shape, heavy and solid like a pearl. It is a specialty of Zhejiang, mainly produced in areas like Shaoxing, Shengzhou, and Xinchang. Because it was historically processed and distributed in Pingshui town, it is also known internationally as “Pingshui Gunpowder Tea.”

Oven-dried Green Tea (Hōngqīng). This tea gets its name from being dried in an oven after the fixation and rolling steps. Its appearance is not as smooth or tightly rolled as pan-fired green tea, but the leaves are whole with prominent tips and a lustrous green color. The liquor is green and bright, with a mellow aroma and taste. It is categorized by shape into four types: strip-shaped (e.g., Huangshan Maofeng), pointed (e.g., Taiping Houkui), flake-shaped (e.g., Lu’an Guapian), and needle-shaped (e.g., Xinyang Maojian). Additionally, oven-dried green tea is often used as a base for scented teas, such as jasmine or magnolia tea.

Sun-dried Green Tea (Shàiqīng). After fixation and rolling, the fresh leaves are dried using sunlight. Sun-dried green tea generally has a milder aroma, and its liquor and steeped leaves have a yellowish-brown hue. Major varieties include “Dianqing” from Yunnan, “Shanqing” from Shaanxi, and “Chuanqing” from Sichuan. Besides being sold as loose-leaf tea, some sun-dried green tea is further processed into compressed teas for border regions, such as “Qingzhuan” (Green Brick) from Hubei, and “Tuocha” and “Bingcha” (Cake Tea) from Yunnan and Sichuan.

White Tea: The Least Processed Tea Category

White tea is a micro-fermented tea, with a fermentation level of 5% to 10%. It is called “white tea” because its buds and leaves are covered in fine, silvery-white hairs (baihao). After a special process of light fermentation without pan-firing or rolling, the finished tea is blanketed in this downy fuzz, appearing silver-white. The brewed tea liquor is also very pale. However, beyond its appearance, the processing method is the core determinant of what constitutes a white tea.

As the least processed of the six major tea categories, white tea undergoes only two steps: withering and drying. But “fewer” does not mean “simpler.” For example, withering, while similar in form to the sun-drying of green tea—spreading the leaves to lose moisture under specific temperature and humidity to alter their internal compounds—requires precise timing, unlike simple drying.

There are two popular theories regarding the origin of white tea, placing it either in the late Ming or early Qing dynasty. White tea is primarily produced in Fujian province, in areas like Fuding, Zhenghe, Songxi, and Jianyang, with a small amount also produced in Taiwan. Based on the raw material, white tea is divided into bud tea and leaf tea. Bud tea is made exclusively from the large, plump buds of the Dabai tea cultivar, represented by “Baihao Yinzhen” (Silver Needle), which is popular in Hong Kong, Macau, and Southeast Asia. Leaf tea is made from a bud with two or three leaves or from single leaves, and includes varieties like “Bai Mudan” (White Peony), “Gongmei,” and “Shoumei.”

Yellow Tea: The Result of a “Processing Mistake” in Green Tea

Yellow tea is perhaps the least known and most overlooked of the six major tea categories. In terms of fermentation, it is slightly more fermented than white tea, typically between 10% and 20%, classifying it as a lightly fermented tea. It is called “yellow tea” because of a core processing step called “sealed yellowing” (mènhuáng), which imparts a characteristic yellow color to the leaves and liquor, along with a unique flavor. Other than this step, its basic production is similar to that of green tea.

Whether using the steaming method of the Tang and Song dynasties or the pan-firing method from the Ming dynasty onward, preserving the “green” in tea has always been challenging due to the unstable nature of chlorophyll. Over-steaming, insufficient pan-firing temperature, delayed rolling, or piling the leaves for too long after rolling can all cause the tea to turn yellow, resulting in yellow leaves and a yellow brew.

However, tea farmers in Anhui and Hubei gradually discovered that if “yellowed” just right, this tea possessed a sweet, fragrant, and mellow character, offering a smoother and less stimulating drinking experience than green tea. Xu Cishu’s Cha Shu (A Discourse on Tea) notes that yellow tea was very popular among the common people for its ability to “cleanse grease and relieve stagnation.” Once the craft matured, it became a tribute tea for the emperor. During the Qing dynasty, yellow tea entered its golden age, with various regions like Hunan, Hubei, Sichuan, Anhui, Zhejiang, and Guangdong developing their own yellow tea products. Hunan and Anhui became the most prominent producers, and Yueyang in Hunan is even known as the “Hometown of Chinese Yellow Tea.”

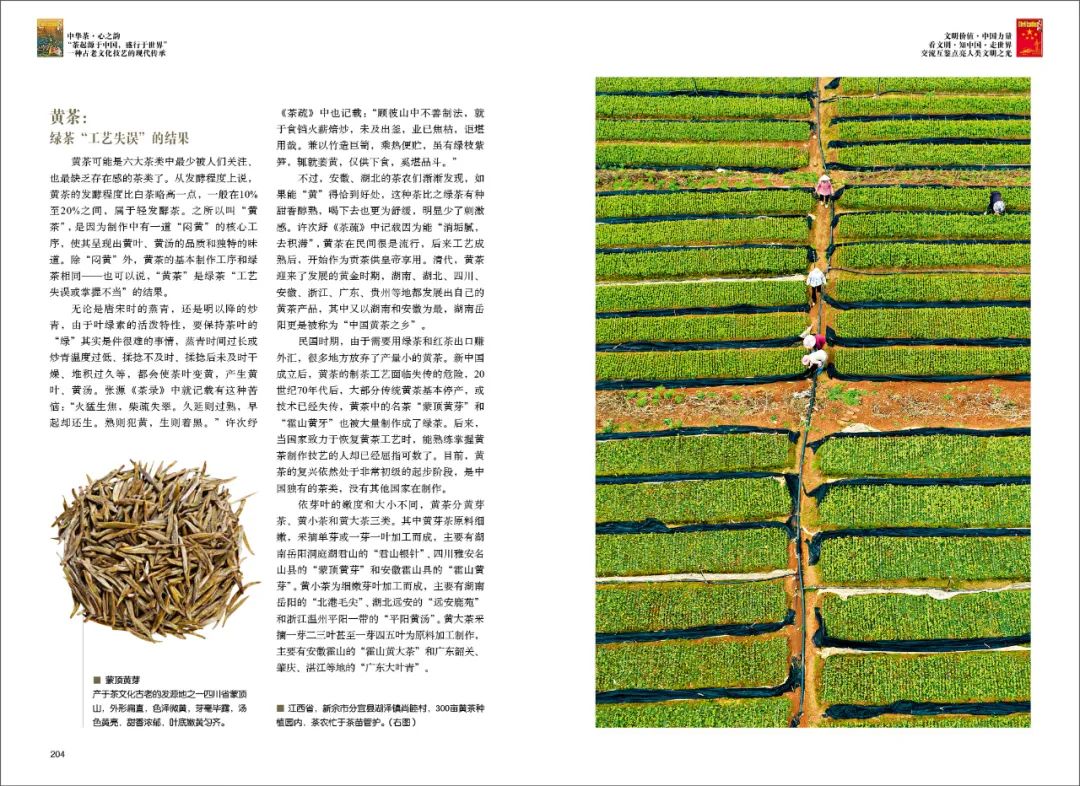

During the Republican era, many regions abandoned the low-volume production of yellow tea in favor of exporting green and black tea for foreign currency. After the founding of the People’s Republic of China, the craft of making yellow tea faced the danger of being lost. After the 1970s, most traditional yellow teas ceased production or their techniques were forgotten. Famous yellow teas like “Mengding Huangya” and “Huoshan Huangya” were largely processed as green teas instead. When the state later made efforts to revive the craft, only a handful of artisans who had mastered yellow tea production remained. Today, the revival of yellow tea is still in its very early stages. It remains a uniquely Chinese tea, not produced in any other country.

Based on the tenderness and size of the buds and leaves, yellow tea is divided into three types: Yellow Bud Tea (made from tender single buds or a bud with one leaf), Yellow Small-Leaf Tea (made from tender young shoots), and Yellow Large-Leaf Tea (made from a bud with two to five leaves).

Oolong Tea: The Most Diverse Tea Category

Oolong tea’s fermentation level falls between that of green and black tea, ranging freely from 8% to 75% depending on the desired outcome. This flexibility has led to a vast diversity within the oolong category. Many famous teas we hear of, such as Tieguanyin, Baijiguan, Rougui, Tieluohan, Fenghuang Dancong (Duck Shit Aroma), Shuixian, and Dongding Oolong, all belong to this category.

It’s worth noting that while modern tea science generally equates “Qingcha,” “Oolong tea,” and “semi-fermented tea,” this was not always the case when the six-category classification was first proposed. At that time, “Qingcha” referred to the processing method, “Oolong” specifically to a tea cultivar, and “semi-fermented” was merely a description of the result. The terms were not interchangeable. Their current synonymous usage is closely tied to the spread and popularization of oolong tea.

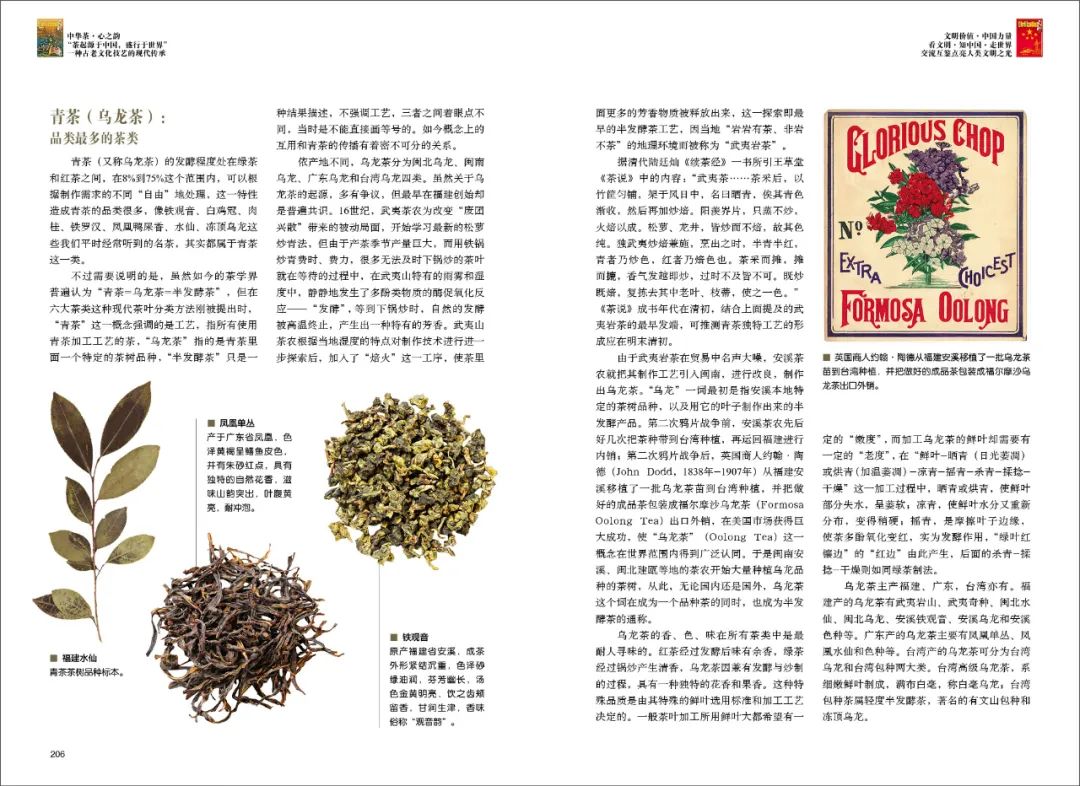

Based on their origin, oolong teas are classified into four main types: Northern Fujian (Minbei) Oolong, Southern Fujian (Minnan) Oolong, Guangdong Oolong, and Taiwan Oolong. Although the exact origin of oolong is debated, it is widely agreed that it first appeared in Fujian.

In the 16th century, tea farmers in the Wuyi Mountains, seeking to adapt to the shift away from compressed tea, began adopting the latest Songluo pan-firing technique for green tea. However, due to the massive output during the harvest season, the time-consuming pan-firing process meant many leaves had to wait their turn. During this wait, in the unique misty and humid climate of Wuyi, the leaves quietly underwent enzymatic oxidation of their polyphenols—a natural “fermentation.” When they were finally pan-fired, the high heat halted this process, creating a unique aroma. Wuyi tea farmers further refined the technique based on local humidity, adding a “baking” (bèihuǒ) step, which released even more aromatic compounds. This pioneering exploration resulted in the first semi-fermented tea, known as “Wuyi Rock Tea” (Wǔyí Yánchá) due to the local geography where “tea grows on every rock, and only on rocks is it true tea.”

As Wuyi Rock Tea gained fame through trade, farmers in Anxi (in Southern Fujian) adopted and modified its production methods to create their own oolong tea. The term “Oolong” originally referred to a specific local tea cultivar in Anxi and the semi-fermented product made from its leaves. Before the Second Opium War, Anxi farmers brought tea seeds to Taiwan for cultivation several times. After the war, British merchant John Dodd transplanted a batch of oolong tea seedlings from Anxi to Taiwan. He packaged the finished tea as “Formosa Oolong” for export, achieving tremendous success in the American market and establishing the term “Oolong tea” worldwide.

Oolong tea’s aroma, color, and flavor are among the most complex and rewarding of all tea categories. While black tea has a lingering fragrance from fermentation and green tea has a fresh aroma from pan-firing, oolong, which undergoes both processes, possesses a unique floral and fruity character. This special quality is determined by its specific standards for fresh leaf selection and its unique processing. While most tea processing favors tender leaves, oolong requires a certain degree of maturity. The process involves withering, cooling, shaking, fixation, rolling, and drying. The key step is “shaking” (yáoqīng), where the leaf edges are bruised to encourage oxidation, creating the signature “green leaves with red edges.”

Black Tea: Born for Trade

Black tea is made from fresh leaves that are withered, rolled (or crushed), fermented, and dried. In terms of fermentation, it is almost fully fermented (close to 100%). Compared to green tea, which has a history spanning millennia and dominates Chinese tea culture, black tea, though originating in China, has a name, dissemination, and culture steeped in foreign influence. It can be said to have been “born for trade,” reflecting a side of foreign trade and cultural exchange that was often overlooked during the Ming and Qing dynasties.

In the 16th century, while green tea reigned supreme, tea farmers in the Wuyi Mountains accidentally discovered that fermented leaves produced a tea liquor with a rich, fragrant aroma. However, this fermented tea was still a far cry from what we define as black tea today.

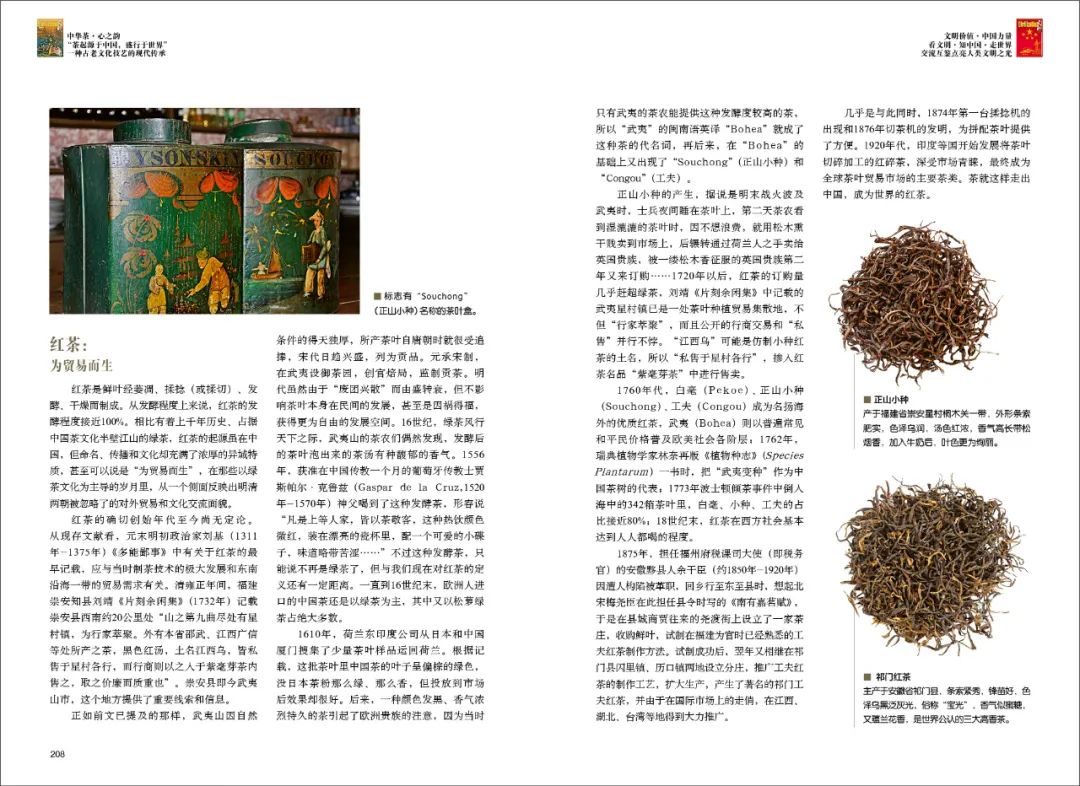

In 1610, the Dutch East India Company shipped small tea samples from Japan and Xiamen, China, back to the Netherlands. Records indicate that the Chinese tea leaves were a brownish-green, less vibrant and fragrant than the Japanese powdered tea, yet they sold surprisingly well. Later, a dark-colored tea with a strong, lasting aroma caught the attention of European nobility. Since only the farmers of Wuyi could supply this highly fermented tea at the time, “Bohea,” the English transliteration of the Minnan pronunciation of “Wuyi,” became its name. Following “Bohea,” terms like “Souchong” (from zhèngshān xiǎozhǒng or Lapsang Souchong) and “Congou” (from gōngfu or Kung Fu) emerged.

The creation of Lapsang Souchong is said to have occurred by chance during the late Ming dynasty. When war reached Wuyi, soldiers slept on piles of fresh tea leaves overnight. The next morning, not wanting to waste the dampened leaves, farmers dried them over a fire of pine wood and sold them cheaply. This tea eventually made its way to British aristocrats, who were captivated by its smoky pine aroma and placed orders for more the following year. After 1720, orders for black tea nearly surpassed those for green tea.

By the 1760s, Baihao, Lapsang Souchong, and Congou had become renowned high-quality black teas overseas, while Bohea became a common, affordable tea enjoyed by all classes in Europe and America. In 1773, nearly 80% of the 342 chests of tea dumped into the harbor during the Boston Tea Party consisted of these black tea varieties. By the end of the 18th century, black tea was a daily beverage for nearly everyone in the Western world.

In 1875, Yu Ganchen, an official from Anhui who was dismissed from his post in Fuzhou, returned to his home province. He established a tea workshop, drawing on his familiarity with the Gongfu black tea methods he had learned in Fujian. Following his initial success, he set up additional workshops in Qimen county, expanding production and creating the now-famous Keemun black tea. Its popularity on the international market spurred the growth of Gongfu black tea production in Jiangxi, Hubei, and Taiwan.

Almost simultaneously, the invention of the first rolling machine in 1874 and the tea-cutting machine in 1876 facilitated the blending of tea. By the 1920s, countries like India began developing CTC (Crush, Tear, Curl) processing for broken black tea, which gained immense market favor and eventually became the dominant type of tea in the global trade market. In this way, tea journeyed out of China, becoming the world’s black tea.

Dark Tea: Born from Trade with Border Minorities

The basic process for dark tea is fixation, rolling, wet-piling, and drying. Dark tea originated when, during green tea fixation, a large quantity of leaves and low fire temperature caused the leaves to turn a dark brownish-green, or when green maocha (unrefined tea) was piled and fermented, turning it black. This process is known as “wet-piling” (wòduī).

According to historical records, dark tea was being produced in Sichuan as early as the beginning of the Ming dynasty’s Hongwu era. Because it developed through the “Tea-Horse Trade” with border minorities, it was also called “border-sale tea” (fānchá). As this trade expanded, many areas in Hunan began producing dark tea during the Wanli era. Though mostly sold to border regions, some was also sold domestically. Gradually, during the Qing dynasty, Anhua in Hunan became the center of a major dark tea category.

Due to differences in production areas and techniques, dark tea is divided into several types: Hunan Heicha, Hubei Laoqingcha, Sichuan Biancha, Dian-Gui Heicha, and Yunnan Pu’er.

Guangxi Liubao Tea, named after Liubao Township in Cangwu County, Guangxi, is a notable example. The Cangwu County Gazetteer, compiled during the Kangxi era of the Qing dynasty, notes: “Tea is produced in Duoxian and Liubao townships. The flavor is mellow and does not spoil overnight; its color, aroma, and taste are all excellent.” The fact that the tea’s flavor “does not spoil overnight” suggests that a dark tea production method was already in use by the early Qing dynasty. During the Jiaqing era, Liubao tea was listed as one of China’s famous teas. In the late Qing dynasty, social unrest led many Chinese laborers to seek work in Southeast Asia (Nanyang). Liubao tea, known for its cooling, digestive, and stomach-soothing properties, and its ability to be stored long-term, became highly prized by the Chinese diaspora, gradually influencing the tea-drinking trends in Malaysia, Singapore, and other regions.